What Our Colonial Legacy Can Teach Us about Immigration Policy Reform

By Gaby Sanchez (MPP Candidate ‘22)

In 1998, the Ecuadorian financial crisis caused severe inflation, bank closures, and a sovereign debt crisis. This caused unrest in the streets and led to a coup d’état, further destabilizing the small Andean country. A few years later, my family and I became a few of the many who participated in the great exodus to the US, Chile, and Spain. Financial instability spread throughout the Latin American region. Along with Ecuador, Mexico also experienced an economic collapse in 1995, meanwhile civil wars in El Salvador and Central America were just coming to an official end.

Others like my family have come to the Global North in trains (la Bestia), boats, like the ones crossing the Mediterranean, in the back of trunks, through smugglers, and on foot. In addition to devastating poverty and lack of opportunities, many are also fleeing prosecution, violence, and political instability.

Currently, immigrants in the U.S. make up 13.7% of the population. California has the largest share of mixed-status families, meaning at least one member of the family is a greencard holder or a U.S. citizen, and at least one other member is undocumented. Despite the Trump administration’s attempt to curtail immigration by building more physical barriers, separating families at the border, and forcing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico during their asylum proceedings, immigrants continue to make the trip to the U.S., usually because the certain dangers at home are outweighed by the possibilities of opportunity in destination countries.

Seeing people being pushed to leave behind their cultures and families made me wonder about how these circumstances came to be. It is no secret that the Global North has firsthand contributed to establishing the economic legacies that the Global South continues to grapple with. Through policies and politics that favored large landowners and deepened economic inequality, colonial and authoritarian regimes of the past can be linked to current migration patterns from Central America. Furthermore, polarized class structure, systemic oppression of indigenous people, lack of infrastructure, mono-cropping, and extreme wealth inequality, also have origins in colonial rule.

More recently, the colonial legacies have continued with unfair trade agreements and foreign intervention in civil wars. In Mexico, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) allowed for cheap, subsidized U.S.-produced corn to flood Mexican markets, further displacing local producers. The U.S. provided military funding and assistance to the right-leaning government in El Salvador during its civil war, which claimed the lives of more than 75,000 people, most of them non-combatants. Unfortunately, the odds were stacked up against the Global South from the beginning, and the playing field has never been evened out.

The economic migrant is usually excluded from any protection, their stories often not highlighted as reasons for humane immigration policies. But isn’t poverty a form of violence? Isn’t having to send one of your children to a foreign land because you can’t afford to feed your family a form of violence? Isn’t a lack of access to hospitals, schools, and social services a type of violence? With poverty comes people trying to desperately survive, which can often mean tensions within households, crime, and violence.

Yet, U.S. lawmakers expect folks to “wait their turn” and use legal avenues to migrate to the U.S. The American Immigration Council explains it best: “Many people wonder why all immigrants do not just come to the United States legally or simply apply for citizenship while living here without authorization. These suggestions miss the point: There is no line available for current unauthorized immigrants and the ‘regular channels’ are largely not available to prospective immigrants who end up entering the country through unauthorized channels.”

The three avenues available to legally enter the U.S., employment, humanitarian, and family reunification, may not be available to undocumented folks living in the U.S., even if they have lived here for decades and have U.S. citizen family members. For example, under current U.S. law, someone who entered illegally cannot be eligible to adjust their status through a legal resident or U.S. citizen family member. This was the case for a client I worked with, whose husband and daughters are U.S. citizens. However, if her husband wanted to adjust her status, she would have to wait 10 years in Mexico. There seemed to be no reason for this other than punishment – punishment for fleeing poverty and instability and punishing U.S. citizens for having undocumented family members. As the main caretaker for her children, who required around the clock care, her absence would deeply disrupt the family structure. While my office was able to petition to waive this requirement, many are not able to and have to choose between leaving their family behind or continue to live undocumented. For low-skilled folks living outside of the U.S., there is little opportunity to migrate legally.

The current U.S immigration law leaves many to fall through the cracks. Without any legitimate and adequate avenues to immigrate safely, migrants will continue to make their trips up north by irregular avenues, where they face the possibilities of kidnapping, exposure to the elements, and abuse by authorities.

Even though immigrants and their families make up a significant portion of the U.S. population and foreign born workers contribute about $2 trillion to the GDP – undocumented workers contribute to 2.6% of the GDP – there are no comprehensive avenues for immigration benefits.

Since the failure of the 2013 senate bill, which was shut down by the Republican-controlled house, there has been no viable option for immigration reform. This bill would have created a path to citizenship for many in the U.S. living without documentation. With the failure of this bill, the Obama administration turned to the authority of the executive branch to create some short-term solutions. However, Deferred Action for Child Arrivals (DACA), Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) – which protected undocumented parents of U.S. Citizens from deportation – and the lesser-known Central American Minors Program, have been mere Band-Aids for this complex issue. These programs provide temporary protections, but the constant attacks by the Trump administration has shown their inherent weakness: immigrant communities will not be safe until they are truly and fully protected in the same manner as U.S. citizens (this is not to say that all U.S. citizens are treated equally). This dynamic leaves vulnerable populations, composed of folks fleeing from poverty and violence, in limbo and further exposed to exploitation.

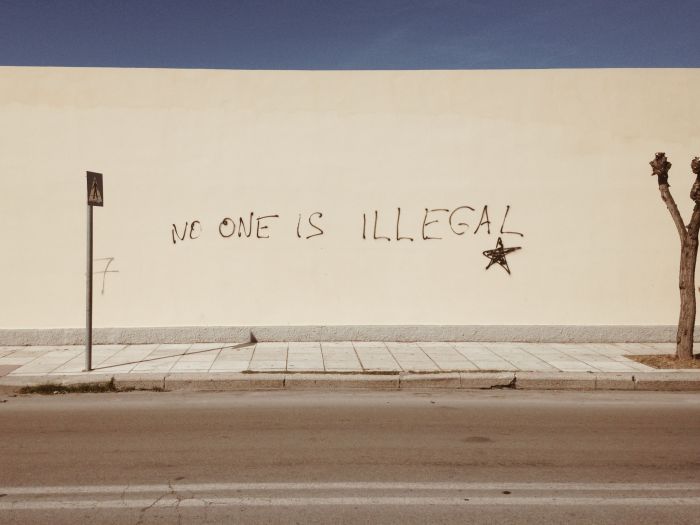

There is some hope, however. The incoming Biden-Harris administration has a long wish list of immigration policy reforms. Campaign promises include ending the family separation policy, ending the policy of forcing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico, allowing family members of U.S. citizens and greencard holders to travel to the U.S. on temporary visas while their family reunification application is processed, and creating a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. While this is promising, both Biden and Harris hold less than stellar records in immigration. Harris collaborated with ICE during her time as San Francisco’s District Attorney, turning over juveniles who had been arrested and suspected of committing a felony to federal authorities. As vice-president to Obama, commonly referred to as Deporter in Chief among immigrant rights’ activists, Biden will also have to reckon with this past. We must hold them accountable; we must ensure that they learned from their mistakes of the past. It is imperative that policy makers understand that global inequality, which has deep roots in colonial systems, drives migration and continues to harm communities and separate families. The Global North cannot ignore its role in the circumstances that people in the Global South grapple with. No walls, or militarization of borders will address the push and pull factors that migrants face.

_142_150_80.jpg) Gaby Sanchez is an MPP candidate ’22 and was born in Guayaquil, Ecuador and immigrated to the San Francisco Bay Area as a child. In 2016, she graduated from Mills College and did her thesis on US refugee policies towards Latin America, which was awarded the Lawrence Shader Prize. She has dedicated her young career to working with immigrant communities in the International Rescue Committee and the American Civil Liberties Union, where she worked on high-profile cases such as the Muslim ban and family seperation. Before attending Goldman, Gaby worked with capitally charged clients as a mitigation specialist with the Community Resource Initiative, where she learned about how the US immigration system and criminal justice system interact. She is pursuing a MPP from Goldman to learn more about immigration policy and international policy and development.

Gaby Sanchez is an MPP candidate ’22 and was born in Guayaquil, Ecuador and immigrated to the San Francisco Bay Area as a child. In 2016, she graduated from Mills College and did her thesis on US refugee policies towards Latin America, which was awarded the Lawrence Shader Prize. She has dedicated her young career to working with immigrant communities in the International Rescue Committee and the American Civil Liberties Union, where she worked on high-profile cases such as the Muslim ban and family seperation. Before attending Goldman, Gaby worked with capitally charged clients as a mitigation specialist with the Community Resource Initiative, where she learned about how the US immigration system and criminal justice system interact. She is pursuing a MPP from Goldman to learn more about immigration policy and international policy and development.

Which degree is right for you?

Which degree is right for you?

Master of Public Policy

Master of Public Policy

Master of Public Affairs

Master of Public Affairs

Doctoral Program

Doctoral Program

Undergraduate Programs

Undergraduate Programs

Global and Executive Programs

Global and Executive Programs

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

Student Groups

Student Groups

Alumni

Alumni

Directories

Directories

Faculty

Faculty

Publications

Publications

Working Papers

Working Papers

Centers

Centers

News Center

News Center

Employment Stats

Employment Stats

Career Advising

Career Advising

Career Resources

Career Resources

Client-based Projects

Client-based Projects

For Employers

For Employers

About GSPP

About GSPP

Events

Events

Make a Gift

Make a Gift

Find a Program

Find a Program

Find a Faculty Member

Find a Faculty Member

Find a Center

Find a Center